Paradise Lost by John Milton

Hello and welcome to The Young Reader’s Review ! It’s that time of year: summer is slowly beginning to tire, autumn is faint-heartedly stepping onto the stage and we are all starting to recalcitrantly settle back into the monotony of the passing days at work, or, in my case, at school, perhaps taking a weary and desperate look every once and a while at the calendar to count the days until we will be able to, once again, momentarily forget our daily routine. Notwithstanding this, with a couple hundreds of pages bound into a book, you can submerge yourself into any other world at any given moment.

If you follow my blog on Instagram (@theyoungreadersreview), you probably noticed that, this summer, I tried to challenge myself by striving to push my limits in the matter of what I read (feel free to share what you read this summer in the comment section!) Therefore, I comprised a list of all of the books that daunted me the most and the first work that made its name on this list was the one that I am going to review today: the legendary and one and only Paradise Lost by John Milton, an author whose influence on English literature is said to be only second to Shakespeare’s.

“Unnerving” would be tragically euphemistic: you open the book, see the never-ending flow of verse, attempt to read and realize that you have absolutely no idea what you just read. Now, you might be wondering what Paradise Lost, a long poem that is an object of worship in English literature, is actually about. Well, the plot itself is quite simple: it’s ten thousand lines of verse, divided into twelve books about the Rise and Fall of Adam and Eve, or in other words, the Fall of Man. But it would be a shame not to delve into the many strata of symbols that hide behind each verse, tempting you (pun intended), teasing you, almost daring you to go beyond their literal sense.

Already, nineteen-year-old Milton, studying at Christ’s College, Cambridge, had declared to his comrades that he would write an epic poem that would rival those of Homer and Dante, even though he would only write Paradise Lost thirty years later. At Milton’s epoch, the epic form was considered to be an outdated literary genre. Since Milton imitates in this long poem the style of great epic authors, Paradise Lost is considered to be what we call a “secondary epic”. Many years later, Milton writes in the section The Verse that precedes the text of Paradise Lost: “The measure is heroic verse without rhyme, as that of Homer in Greek, and of Virgil in Latin”. Milton’s writing style does indeed follow the that of classical epic poems. First, Paradise Lost is composed in long Latinate sentences that are comprised of many juxtaposed and subordinate clauses and that extensively use enjambment (“(in verse) the continuation of a sentence without a pause beyond the end of a line, couplet or stanza”- Oxford Dictionaries), giving the impression of an unremitting, breathless flow of words. This refusal to end-stop corresponds to a refusal to let a line coincide with a syntactical unit of meaning. Also, Milton’s meter is written in unstable iambic pentameter even though we could more or less say that Paradise Lost is written in the blank verse popularized by playwright Christopher Marlowe (1564-1593).

The first verse of Paradise Lost is already rebelling against the traditional laws of poetic meter by beginning with a stressed syllable: “Of man’s first disobedience”. It’s a “double disobedience” of sorts. Moreover, this long poem is the first narrative poem in English to have been written in unrhyming verse (more specifically blank verse since it is in fact written in iambic pentameter). But this shouldn’t surprise the reader since, Milton tells us in the first sixteen lines of verse that Paradise Lost will pursue “Things unattempted yet in prose or rhyme”.

To give you a sneak-peak of this verse, here is the first verses, constituting the beginning of book I of Paradise Lost:

Of man’s first disobedience, and the fruit

Of that forbidden tree, whose mortal taste

Brought death into the world, and all our woe,

With loss of Eden, till one greater man

Restore us, and regain the blissful seat,

Sing heavenly muse, that on the secret top

Of Oreb, or of Sinai, didst inspire

That shepherd, who first taught the chosen seed,

In the beginning how the heavens and earth

Rose out of chaos: Or if Sion hill

Delight thee more, and Siloa's brook that flowed

Fast by the oracle of God; I thence

Invoke thy aid to my adventurous song,

That with no middle flight intends to soar

Above the Aonian mount, while it pursues

Things unattempted yet in prose or rhyme.

Milton was a political revolutionary: he had participated with zeal to the establishment of England’s new non-monarchic government. He believed that England could only be ruled without the dictatorial intervention of a sovereign power, contrarily to the principals of, for example, the social contract theory which Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679, philosopher), Milton’s slightly older contemporary, extols in Leviathan. Milton’s political principals were closer to the ideals of John Calvin (1509-1564, French theologian, pastor and reformer). Therefore, Milton had consistently thought that his poem would be on a nationalistic theme that would resemble Spenser’s Faerie Queene or Virgil’s Aeneid. Perhaps the choice to diverge from this theme came from the fact that Milton wrote Paradise Lost after the revolution had failed and after he had gone through the defeat of his utopian Puritan government. Something that I found fascinating in Paradise Lost is the continual analogy that associates Eden, the paradise that “Man lost”, with this utopian government that “England lost”. The word “error” is actually one of the most used words in Paradise Lost and British literary critic scholar Christopher Ricks argues that this use was intentional in order to show that Eden, or England, was, in a way, already doomed. Milton was under pressure since his description of Eden would necessarily be a political statement as any 17th century depiction of Eden at the time. Eden is the reference for fallen utopias and Milton, through his description of this paradise, strives to denounce the arbitrary declaration of hierarchal supremacy. Also, it is important to take note that, according to Christian beliefs, except for Adam and Eve, mankind has never known Eden. Consequently, describing Eden is essentially describing the indescribable. Nevertheless, many university professors such as Yale professor John Rogers, believe that the most captivating facet of these twelve books is the parallel with Satan. And so do I.

You don’ t read Paradise Lost for Adam and Eve; you read Paradise Lost for Satan. This might seem surprising since Milton was an ever so pious Puritan but strangely enough Satan is in fact the most interesting and charismatic character in Paradise Lost. Satan is the character that has the most rhetorical vigor, that manages to make the reader empathize for him when he is banished from Heaven and whose words resonate with a haunting attractiveness. He is probably the closest there is to a “hero” in Paradise Lost. Also, just like Satan, we technically only know “fallen Eden”: we will never know Eden’s innocence and we see the same “undelighted all delight” (l.286 book IV) as this character does. So, in a way, Satan is the character that we are the most similar to in this poem. This surprising ambiguity consequently created might make the reader uneasy since no clear “moral base” is established; “good” and “bad” seem intertwined and even interdependent. This can be for example provoked by this sentence Satan pronounces in book IV:

“[…] all good to me is lost; Evil be thou my good”

Or the very famous and powerful:

"Better to serve in hell, than serve in heaven" (book I)

This could also make us realize that “good” cannot exist without “evil”; God for instance purposely lets Satan establish himself first in Hell and then on Earth so that human beings could fight against him. Milton makes it difficult for us, the reader, to discern “right” from “wrong”.

Moreover, the fact that the most absorbing books of Paradise Lost were the ones that are centered around Satan troubled the readers of that time. On the one hand, William Blake (1757-1827) wrote that:

“The reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels and God, and at liberty when of Devils and Hell, is because he was a true Poet and of the Devil’s party without knowing it”.

He therefore insisted that Milton was unconsciously glamorizing Satan since tends “true” poetry tends to do so. On the other hand, Shelley (1792-1822

) interpreted this differently and said that:

“This bold neglect of a direct moral purpose is the most decisive proof of the supremacy of Milton’s genius.”

Shelley suggests that the positive connotations revolving around Milton’s Satan were entirely deliberate and that this capacity of disassociating morality from poetry is what proves Milton’s genius.

One of the themes that interests me the most in Paradise Lost is the representation of Eve and, by extension, Milton’s representation of women. Virginia Woolf’s image of Milton is probably the image that is the most rooted in the mind of today’s reader: she called him “the first of the masculinists”. The representation of Adam and Eve in Paradise Lost is Milton’s portrayal of how all human relationships should be. Reading Paradise Lost today, as a woman who lives in a world where feminist movements are widespread, is a strange experience to say the least since Milton forces his female reader to accept their subordinate place in society. In book IV, the description of Adam and Eve begins as almost being egalitarian until the lines:

“(…) though both

Not equal, as their sex not equal seemed

(…) He for God only, she for God in him”

These lines truly shocked me. Eve’s submission to Adam can also be found small details, even in the description of Eve’s hair:

“Her unadorned golden tresses wore

Dishevell’d, but in wanton ringlets wav’d

As the Vine curls her tendrils, which impli’d

Subjection, but requir’d with gentle sway ,

And by her yielded, by him best reciev’d,

Yielded with coy submission, modest pride,

And sweet reluctant amorous delay.”

Yet, despite this sexist-seeming delineation, there is a debate among Miltonists if this isn’t in fact free indirect speech from Satan. This explanation would bring comfort that Milton isn’t telling us that the social organization of Eden is sexist but that the patriarchy is satanic. In my opinion, I find this theory to be a little far-fetched since the sexism in this poem is omnipresent but this matter is still left open to interpretation.

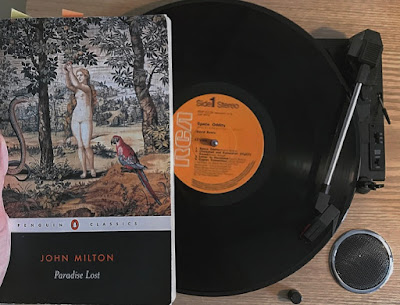

Now, you might be thinking “That seems very interesting and all but why should I read this four-hundred-year-old poem that spans along twelve books”? Well, the exquisite composition of the poetry, the depth of the characters and the range of the themes Milton touches in Paradise Lost make that you don't have to necessarily be interested in the "justification of the ways of God to men" in order to read this. The only thing that I must underline is that I highly recommend buying an academic addition of Paradise Lost ( I personally have the Penguin Classics edition) since the footnotes can not only be interesting, but can also aid you in your comprehension of the language, plot and symbols.

Now, you might be thinking “That seems very interesting and all but why should I read this four-hundred-year-old poem that spans along twelve books”? Well, the exquisite composition of the poetry, the depth of the characters and the range of the themes Milton touches in Paradise Lost make that you don't have to necessarily be interested in the "justification of the ways of God to men" in order to read this. The only thing that I must underline is that I highly recommend buying an academic addition of Paradise Lost ( I personally have the Penguin Classics edition) since the footnotes can not only be interesting, but can also aid you in your comprehension of the language, plot and symbols.

That is it for today’s review! I hope that you enjoyed it and that you will now run on over to the closest bookstore in order to delve into the majestic Paradise Lost. If you have any questions, comments or recommendations feel free to leave a comment in the comment section below. Don’t forget to follow this blog on Instagram (@theyoungreadersreview) and to go check out my poetry and creative writing Tumblr ( http://theinscrutableescapee.tumblr.com/ ). Have a great day and see you next time for another review! ( -_・)

© Margaux Emmanuel 2018

Comments

Post a Comment